Thoughts on Kiarostami

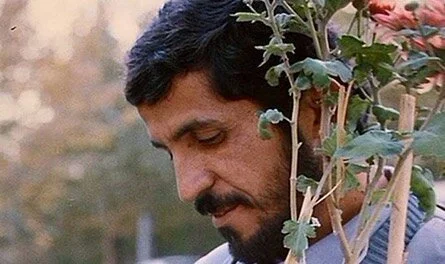

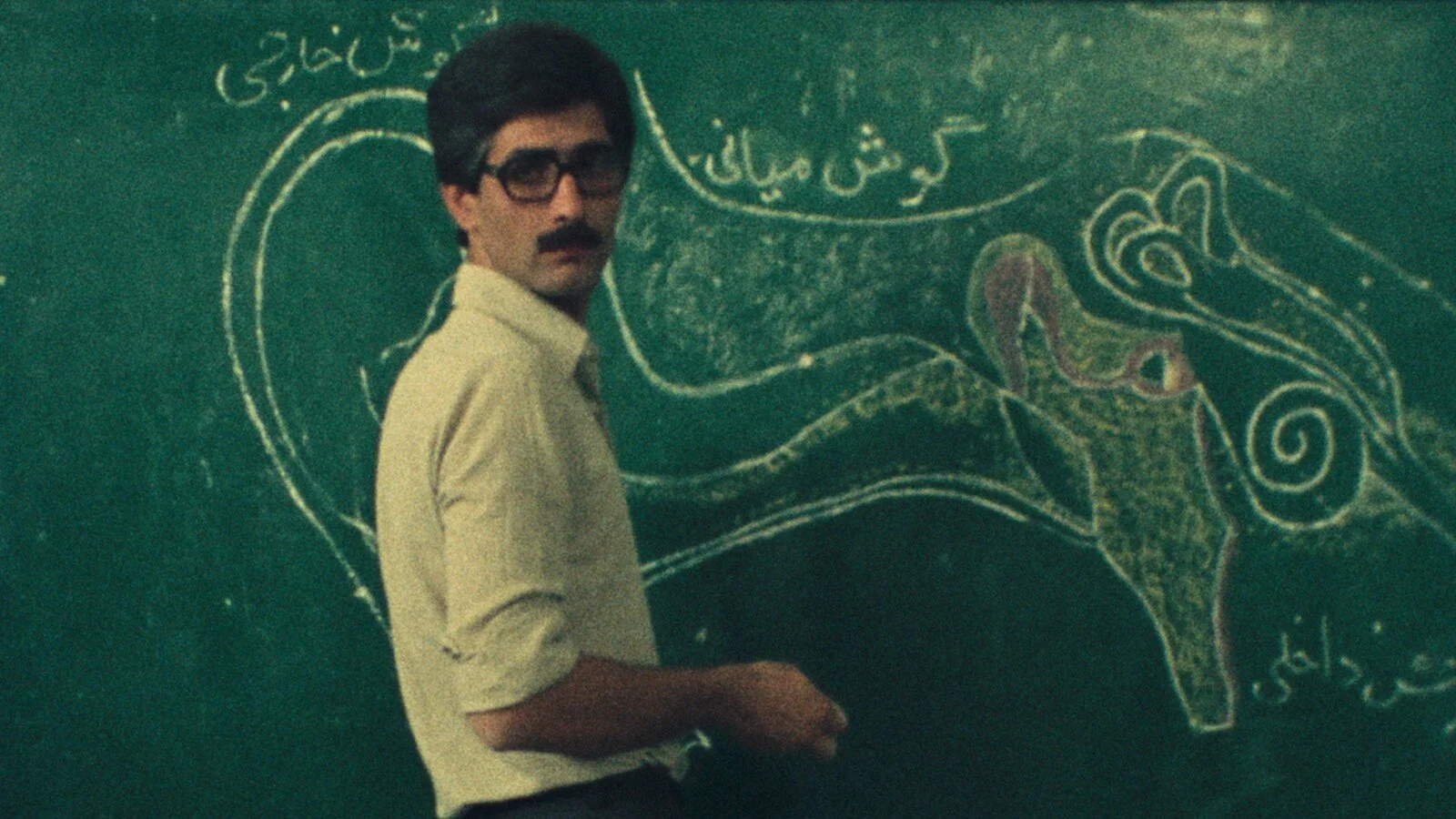

Last year, with the twenty-something retrospectives of Kiarostami’s work, I gave myself over to nearly all of his available film work and much of the critical dialogue surrounding it. The Koker Trilogy, Close-up, Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us define his most satisfying middle period for me.

The early works made under the Shah through Kanoon demonstrate a remarkable capacity for poetry and politics in the face of censorship. Of this period First Case, Second Case and Fellow Traveller stand out as conceptually driven, politically oriented films that provoke critically. His late period of experimental works feel overdetermined in their postmodern constructions.

The middle period is his most fertile for the issues closest to me; those of form, knowledge, Truth, class, otherness and the ethnographic gaze. These slow meditative pieces open up into moments of startling beauty, with small quotidian acts of kindness serving as the main events. The films have a delicate balance of self-reflexivity, caprice, beauty and philosophy.

For anyone who has seriously considered suicide, Taste of Cherry is a generous, unresolved offering. Kiarostami called his films ‘half-made’ for their openness to interpretation and I found viewing them at screenings with conversation following, they shimmer like prisms, reflecting differently to each.

In Iran, Kiarostami has been criticized for many things, including a kind of exoticizing, orientalist, obscurant approach inflected towards international audiences. From my occidental, artistically-biased position I find myself justifying his move towards a philosophical realm that inevitably forfeits a degree of context and particularity in service of opening a space hospitable to more disparate and alienated subjectivities.

Mehrnaz Saeed-Vafa in conversation with an often-tedious Jonathan Rosenbaum— and interrupted by September 11th—provided me with a good companion reader. Another interesting piece of scholarship by Matthew Abbott, focusing on Kiarostami’s late period, elaborates the advanced uncertainty of postmodernism and offers a vocabulary of Kiarostami’s ambiguity. Abbott’s epistemic ambivalence, cool to enlightenments rage to know, relaxes into an unresolved presence in viewing.

In Godfrey Cheshire’s Conversations with Kiarostami, we find the later director aloof, condescending, manipulative, arrogant and generally thankless to his collaborators over the years.

The question of how to how to situate his films in relation to social and political justice in Iran and the representation of women in Kiarostami casts into sharp relief, my cultural naiveté. This marks the beginning of an exploration.

Social media mention 1/20